Exegetical History: Nazis at the Round Table—Martin Shichtman and Laurie Finke

Shichtman: Departments of Jewish Studies and of English Language and Literature, Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti, MI

Finke: Department of Women’s and Gender Studies, Kenyon College, Gambier, OH

Abstract

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 2 Some might argue that when Nazis fantasize themselves as medieval knights, they debase a beautiful, noble, and innocent past. They might insist that this fantasy, which feeds a desire to see the male body as larger than life, this fetishizing of the body as armor and muscle, may be perverse, but the ideal–the chivalrous knight who pledged himself to honor, loyalty and brotherhood—should not be tarnished by that perversion. This essay, however, explores the possibility that there is, in all imaginings of the knight, always the potential for fascist desire. It suggests that there may be an unsavory kinship between the armored warriors of medieval Europe—even the romanticized armored warriors of King Arthur’s court—and the armored divisions of Nazi blitzkrieg. A fascist aesthetic is the darkness at the heart of Arthurian history, especially as it celebrates aggressive hypermasculinity mobilized in the service of a persecuting society intent upon domination.

Article

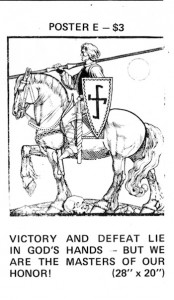

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 1 In a 1970s brochure from the National Socialist White People’s Party, found in the University of Michigan’s Labadie Collection archive, there are advertisements for poster-sized pictures. Most of these posters have distinctly Nazi themes: German soldiers and pictures of Hitler—there is even a two for one deal, offering both a portrait of Hitler and a photograph of the door to his home. One of the posters appears, at first glance, unremarkable, resembling the kinds of pictures often gracing the walls of male teenagers—comic book drawings of heavy-metal muscle-men, and sometimes women, engaged in, preparing to engage in, or triumphantly returning from some sort of battle against a generally unspecified enemy. The National Socialist White People’s Party poster portrays the profile of an armored man on horseback (see Figure 1).

¶ 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0

Courtesy Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Library)

Courtesy Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Library)

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 [Figure 1]

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 1 While not quite as Schwartzeneggerian in physique as the figures on some other posters, the knight is muscular, riding atop a mammoth horse that tramples the bones of those who have fallen in whatever battle he recently fought. He sits proud, magnificent, majestic, a figure from a distant past, nostalgically recollected. On the knight’s shield there is a swastika, suggesting not so much his political position (Could a medieval knight possibly have a modern political position?) but rather his Aryan racial heritage and identity; this ‘coat of arms,’ the National Socialist White People’s Party would have us believe, places the knight among world conquerors, uncorrupted and incorruptible, übermenschen. The poster’s caption reads ‘Victory and defeat lie in God’s hands—but we are masters of our honor.’ This poster is copied from a woodcut that originally appeared in Die Kunst im Dritten Reich (Art in the Third Reich), described by Anthony Rhodes as the ‘most elaborate’ of the art journals produced by the Nazi regime, ‘beautifully laid out, with paper and color plates of the highest quality’ (Rhodes, 1976, 25). It recalls Nazi artist Hubert Lanzinger’s painting, ‘The Flagbearer,’ in which the Fürhrer, likewise in profile, armored and on horseback, holds the large swastika flag of the Third Reich (Finke and Shichtman, 2004, 188; Golomshtok, 1990). How necessary is it for the swastika actually to be pictured in order that the knight function as a player in fascist fantasy?

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 2 Some might argue that when alienated white male teenagers with Nazi sympathies fantasize themselves in knightly dress, they debase a beautiful, noble, and innocent past—just as they would argue that Lanzinger debased that past in his painting. They might insist that this fantasy, which feeds a desire to see the male body as larger than life, this fetishizing of the body as armor and muscle, may be perverse, but the ideal—the chivalrous knight who pledged himself to honor, loyalty and brotherhood—should not be tarnished by that perversion. This essay, however, explores the possibility that there is, in all imaginings of the knight, always the potential for fascist desire.[1] It suggests that there may be an unsavory kinship between the armored warriors of medieval Europe—even the romanticized armored warriors of King Arthur’s court—and the armored divisions of Nazi blitzkrieg. A fascist aesthetic is the darkness at the heart of Arthurian history, especially as it celebrates aggressive hypermasculinity mobilized in the service of a persecuting society intent upon world conquest.

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 In ‘Fascinating Fascism,’ Susan Sontag argues that a ‘fascist aesthetic’ flows from and justifies

situations of control, submissive behavior, extravagant effort, and the endurance of pain; [it] endorse[s] two seemingly opposite states, egomania and servitude. The relations of domination and enslavement take the form of characteristic pageantry: the massing of groups of people; the turning of people into things; the multiplication or replication of things; the grouping of people/things around an all-powerful, hypnotic leader-figure or force. The fascist dramaturgy centers on the orgiastic transactions between mighty forces and their puppets, uniformly garbed and shown in ever swelling numbers. Its choreography alternates between ceaseless motion and a congealed, static, ‘virile’ posing. Fascist art glorifies surrender, it exalts mindlessness, it glamorizes death. (Sontag, 1980, 91)

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 2 Such an aesthetic is, Sontag argues, by no means confined to the politics of the radical right. In fact, it might be more accurate to call it a totalitarian aesthetic. The ‘features of fascist art proliferate in the official art of communist countries … The tastes for the monumental and for mass obeisance to the hero are common to both fascist and communist art, reflecting the view of all totalitarian regimes that art has the function of “immortalizing” its leaders and doctrines’ (Sontag, 1980, 91). It is articulated as early as 1909 in the Futurist Manifesto of Filipo Tommaso Marinetti, cited by Walter Benjamin in his epilogue to ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’:

War is beautiful because it establishes man’s dominion over the subjugated machinery by means of gas masks, terrifying megaphones, flame throwers, and small tanks. War is beautiful because it initiates the dreamt-of metalization of the human body. War is beautiful because it enriches a flowering meadow with the fiery orchids of machine guns. War is beautiful because it combines the gunfire, the cannonades, the cease-fire, the scents, and the stench of putrefaction into a symphony. War is beautiful because it creates new architecture, like that of the big tanks, the geometrical formation flights, the smoke spirals from burning villages, and many others. (Marinetti, 1909, cited in Benjamin, 1986, 241)

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 3 Marinetti’s aestheticization of war, written in celebration of fascist Italy’s aggression against Ethiopia, reflects sentiments that were already circulating in intellectual circles throughout Europe and the United States. The passage suggests that techniques invoking hypermasculinity, violence, aggressive imperialism, and surrender to authority have had a long history in Western visual culture. And the aesthetic continues to circulate, appearing in works like Walt Disney’s Fantasia, Busby Berkley’s The Gang’s All Here and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 (Sontag, 1980, 91), as well as in movements as diverse as ‘youth/rock culture, primal therapy, anti-psychiatry, Third World camp-following, and the belief in the occult’ (Sontag, 1980, 96). The attraction of the fascist aesthetic resides in its idealism: ‘the ideal of life as art, the cult of beauty, the fetishism of courage, the dissolution of alienation in ecstatic feelings of community; the repudiation of the intellect; the family of man (under the parenthood of leaders)’ (Sontag, 1980, 96). Although obviously medieval knights could not possibly have conceived of themselves as fascists, they embraced an aesthetic (chivalry) that could later be adopted and, arguably, perfected by totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century. It should, therefore, come as no surprise that Nazis would find many points of identification in medieval chivalry.

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 5 The patronage of Arthurian history, as we argued in King Arthur and the Myth of History, reached its zenith during the aristocratic diaspora of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries—the age of the great crusades—when the aristocracy of western Europe embarked on a period of conquest and domination. Though events like the Norman Conquest or the Crusades perhaps lacked the singularity of purpose that characterized Nazi expansionism (such singularity of purpose was perhaps, for reasons we argue elsewhere, not possible during the late medieval period, see Finke and Shichtman, 2004, 94–102), they attest to the sometimes fanatical militarism of the high Middle Ages, a militarism glamorized by the ideals of chivalry. This period, not surprisingly since it was a time in which political boundaries were changing, was also marked, as R. I. Moore (1987) and John Boswell (1980) have both noted, by a growing intolerance and even persecution of those who lay outside of the dominant hegemony. While Boswell documents growing state and Church persecution of same sex love, Moore explores the creation of the ‘persecuting society’ in the high Middle Ages’ treatment of heretics, lepers, and Jews. The literature of chivalry, patronized by the same aristocracy that was so intent on expanding its territories, could not have glorified the knight as the agent of official state and church persecution. It had to displace that persecution into fantasy. King Arthur could hardly achieve heroic stature by riding around the countryside dispatching bands of peasants, lepers, and Jews. As the representative of the forces of order and religion, Arthur must triumph over more menacing and hence more prestigious foes, as, for instance, when he defeats the Mont St. Michel giant on his way to conquer Rome (Finke and Shichtman, 2004, 97–102). Medieval Arthurian romances celebrated the hegemonic masculinity of the warrior at a time when those prerogatives were zealously guarded by rigorous training and arcane rituals of initiation. The events which Arthurian histories displace into such glorious exploits were much more mundane—and considerably more horrific. They included the persecution and massacre of defenseless heretics, lepers, Jews, sodomites, and anyone else who, for whatever reason, threatened the political security of the ruling classes or held possessions desired by them (Moore, 1987). We argued in King Arthur and the Myth of History that medieval aristocrats used the genealogies provided by historical narratives of King Arthur to justify and promote their own, often oppressive, exercise of power. To the extent that the medieval knight was a Deleuzoguattarian assemblage of man, armor, and weapon, he could become a potent symbol for the ‘dreamt-of metalization of the human body.’ Chivalric narratives easily served the needs of twentieth century fascists for markers of genealogical transmission and legitimation.[2]

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 A poster for the 1936 Reichbauerentag (Reich Farmers’ Day) in Goslar suggests how this symbol could be visually deployed for propaganda purposes (Figure 2).

¶ 14

Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0

Courtesy of the German Propaganda Archive at Calvin College

Courtesy of the German Propaganda Archive at Calvin College

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 [Figure 2]

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 6 Although one assumes that the audience for this image would be farmers, the dominant figure is not the farmer, but a colossal knight in medieval armor, carrying a sword and somewhat shadowy shield. Swastikas adorning his breastplate and a twentieth-century military helmet identify him as a modern German soldier. He faces his prospective enemy to the East, represented by the Soviet hammer and sickle in the upper right corner. The knight’s ‘social skin,’[3] his armor, attests to his potency and his impenetrability. His gigantic size is established by comparison with the tiny farmer near the bottom of the picture tending his fields with a horse-drawn plow. The disproportion suggests a modern secular version of the medieval ideology of three orders in which those who fight (bellatores) must protect those who work the land (laborares), such protection almost always amounting to a protection racket, allowing the powerful to dominate the weak. The poster advances the Nazi ideology of blut und boden, blood and soil, a brutal concoction of racialism, militarism, and expansionism. Blut und boden suggests the right of Aryan peoples to claim lebensraum, living space, to displace racial inferiors, by force if necessary, from their property. In the Farmers’ Day poster, the powerful knight and the nearly insignificant farmer join forces, looking back to a glorious past and forward to an even more promising future. The ambitions of the master race are tied up in these two idealized personages, who take control of the land and then cultivate it.

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 This chivalric assemblage occurs early on in the writings of post-World War I Germany’s ultra-right. Erich Edwin Dwinger’s memoir, Die letzten Reiter (The Last Horsemen), rhapsodizes, for instance, on the significance of the Freikorps, right-wing paramilitary groups that emerged in Germany following its defeat in the first world war:

‘One last time,’ he writes, ‘the old days rose again with us; they rose again in three senses! In the military sense first; . . .One last time we fought as true cavalrymen, raising a scarcely remembered weapon, a lance of old, to gleam again. Second, in a material sense: one last time we lived in wide open spaces, spending many of our days with men who called princely estates their own. But the space was taken from us and the Baltic princes fell . . . Third, in the spiritual sense: one last time each of us could be individual, with nothing to constrain his spirit.’ (Theweleit, 1987, 2: 63–64)

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 1 Dwinger, reading his text on several symbolic levels with the fervor of a medieval exegete, suggests that Freikorps ‘history’ is not so much a perversion of the middle ages but rather a successor narrative, a figural continuation of the impulse to romanticize history in order to legitimate—and even glorify—masculine aggression marshaled in the service of state-sanctioned violence. Dwinger laments the ‘end of chivalrous soldiery’ displaced by modernity, by the ascendancy of the masses ‘rolling toward us from East and West’ (Theweleit, 1987, 2: 64).

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 We might simply dismiss Dwinger’s fascination with Germany’s medieval past as an adolescent nostalgia for what never was, as Klaus Theweleit seems to do in Male Fantasies: ‘Not one of the qualities apostrophized by Dwinger in his story of “one last time” has ever pertained to these men. Not the knight’s lance, nor the prince’s table, nor the broad “territory of the world” has ever been theirs—nor, indeed, has the “boundlessness of the individual spirit” (whatever that may be). … The only reality expressed here is that of the youthful dreams of the youth movement’s boyish romanticism, … their dreams of world conquest, fantasies of nobility and King Arthur’s roundtable’ (Theweleit, 1987, 2: 64). But we should not underestimate the power of these fantasies. Dwinger’s Die letzten Reiter similarly offers more than simple nostalgia. If the recollection of an idealized past brought comfort to those for whom the present held dangers and insecurities, it also held out the prospect of mobilizing fascist desire. Dwinger deploys the figure of the chivalric warrior in both his defensive and aggressive postures. For Dwinger, and his Freikorps associates, the knight stands protected from—above—a world reckoned as having spun seriously out of control, a world in which Germany has lost a major war, has been severely punished, humiliated by its conquerors, and has been betrayed both by bureaucratic profiteers—bankers and industrialists—and the masses, vulgar and easily manipulated by greed and self-interest. But the knight also stands prepared to re-claim, by force, all that is rightfully his, his inheritance; he is prepared to recapture all that belonged to him and his kind in ‘the old days,’ prepared to bring about the restoration of a time when men of chivalric orders ruled without question. Dwinger’s knight is armored and armed, determined to repel the conquerors, crush the profiteers, and lead the masses in the direction of righteousness; he is Germany’s salvation.

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 3 For the Nazis and their sympathizers, the knight, representative of Germany’s illustrious past, was a prominent figure for German nationalism and fascist desire. Clashes between the Nazis and the German Freemasons illustrate the ways in which this contested image served as a lightning rod for nationalist discourse. It is relatively common knowledge that that the Nazis persecuted Freemasons; the fraternal organization’s secrecy and international connections fed into beliefs about an international Jewish conspiracy to create a world republic. In Nazi exposés, Freemasons were ‘artificial Jews’ or Jewish ‘tools’ (Melzer, 2004, 89, 93); in concentration camps, Freemasons were classified as political prisoners. During the period between 1925 and 1935, however, Freemasons appropriated the medieval knight, and the Arthurian narratives that glorified him, in the struggle to survive Nazi suppression, turning to medieval chivalric narratives to prove their Aryan credentials.

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 In 1925 there were more than 82,000 Masons in 632 German lodges. They were not a homogeneous lot and responses to the Nazi aggression against them ranged from resistance to collaboration and even fervent belief. A brief foray into the structure of German Freemasonry may clarify these varied responses. In Germany, Masonry was divided into two more or less politically aligned factions. This is significant in itself as Freemasonry was meant to be a fraternal organization of men bound in brotherhood across national boundaries and religious and political beliefs. A fundamental principle of Freemasonry is that members should not discuss either religion or politics in the lodge.[4]The Old-Prussian Grand Lodges, however, participated in the ‘German nationalist milieu’ and ‘for the most part, deliberately excluded Jews from membership.’ The Humanitarian Grand Lodges initiated those who ‘could usually be counted as members of the political parties that were in the middle-left of the political spectrum’ (Melzer, 2004, 90). By the mid-twenties the Humanitarian Lodges were rapidly losing members to the Old-Prussians: ‘Most members of the Old-Prussian lodges and even some members of the few dogmatic Humanitarian lodges did not find the central elements of the Nazi Party’s ideology to be contradictory to their Masonic beliefs’ (Melzer, 2004, 91).

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 For a brief period at the beginning of Hitler’s rise to power, the German Lodges attempted to survive by placating the Nazis, bringing their identities closer in line with Aryan ideologies. ‘Beginning around 1926,’ according to Ralf Melzer, ‘the Grand National Mother Lodge and the Grand National Lodge of Freemasons of Germany showed clear signs that they wanted to separate themselves from Freemasonry’s Jewish and Old Testament traditions’ by adopting more Aryan rituals.[5] They turned to the middle ages to create those rituals, rituals designed to make the fraternity more palatable to Nazi rulers by locating their origins in medieval chivalry. On April 7, 1933, Herman Göring met with the Grand Master of the Grand National Lodge of Freemasons of Germany. Together they formulated a law that reorganized the Lodge:

The order will return to its original shape. From today on, the term “Große Landesloge der Freimaurer von Deutschland” which was taken on in the 18th century will no longer be valid. The order will henceforth have the name that corresponds with its nature: “Deutsch-Christlicher Orden (Gral [added by hand]) der Tempelritter” [German Christian Order (of the Grail) of the Knights Templar]. (Melzer, 2004, 97)

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 2 Other lodges followed soon after. The order stresses a return to an ‘original’ medieval and Christian state associated with the Holy Grail and the Knights Templar that had been corrupted by Enlightenment ideals. On April 23, the German Order of the Knights Templar issued new rules, which ‘as a consequence of the German and Christian character of the order,’ limited membership only to ‘Germans of Aryan origin who have been baptized as Christians,’ refusing membership to anyone whose parents or grandparents were not Aryan and to any person whose wife was Jewish (Melzer, 2004, 97-8). Salutations, titles, and rituals were all revised. The Old-Prussian Lodges stopped using Hebrew expressions, replacing Old Testament narratives with ‘Germanic legends and the mythology of the Holy Grail.’ The Germanic god Baldur replaced Hiram Abif, Strassburg’s cathedral replaced Solomon’s temple.[6] Despite these concessions, by 1935 the Masonic Lodges had all been dissolved, their property confiscated and their halls vandalized, their members either barred from public life or arrested; one lodge, the Symbolic Grand Lodge of Germany, went into exile in Tel Aviv. As Melzer notes, the history of German Freemasonry’s encounter with the Nazis is ‘not only one of persecution but also one of conflict and conformity’ (Melzer, 2004, 101), in which Arthurian mythologies denoted and promoted Aryan purity.

¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 1 There can be little doubt that Arthurian narratives played some part in the Third Reich’s efforts to romanticize—perhaps even mythologize—itself. But it is difficult to determine whether those who fashioned the Third Reich genuinely believed themselves inheritors of knightly chivalric tradition or cynically invoked this tradition because it easily functioned to advance an ideology of conquest and hatred. A number of historians have attempted to force this differentiation—to determine whether Nazism transformed idealism into propaganda or simply was unable to distinguish between idealism and propaganda—and have found themselves uneasily positioned, reading Nazis as Nazis sought to read themselves (see Höhne, 1972, 153-55). For these historians—as with those who research the chivalric codes of America’s Old South—there lurks a fascination with the efforts of sometimes monstrous men to reproduce an antique past we have idealized. However, we believe that this differentiation may be beside the point, that the figure of the knight is continuously at the heart of fascist desire because something akin to fascist desire was continuously at the heart of the figure of the knight, that there is a link between the organized, armored masculine aggression of the middle ages and organized, armed masculine aggression in the twentieth century.

¶ 27 Leave a comment on paragraph 27 2 We read, for instance, in Heinz Höhne’s The Order of the Death’s Head, of Heinrich Himmler’s attraction to things Arthurian. Himmler, who had been a member of the Freikorps, was no doubt indoctrinated into its ideology, no doubt dreamed the same dreams as those recalled by Dwinger. But Himmler’s embrace of the middle ages draws its strength from specificity, from a material recreation of chivalry, rather than from Dwinger’s generalized affection for the ‘old days.’ In 1933 Himmler began renovations on Wewelsburg Castle, a seventeenth-century castle in the district of Paderborn, planning to construct an ideological center for his SS. Wewelsburg Castle stands as a monument to Nazi ideas about chivalry.[7] Two rooms in the north tower of the triangular-shaped castle architecturally realize this ambition to create a new Round Table (see Figure 3).

¶ 28

Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0

Courtesy of Gunther Jönsson, D-31675 Bückeburg, www.flickr.com/photos/40280724@N06

Courtesy of Gunther Jönsson, D-31675 Bückeburg, www.flickr.com/photos/40280724@N06

¶ 29 Leave a comment on paragraph 29 0 [Figure 3]

¶ 30 Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0 The tower crypt was redesigned to be a circular vault with twelve seats at its circumference, representing, some believe, King Arthur and his twelve knights, as well as the twelve departments of the SS. In the middle of the room is a circular feature, a pit, which resembles nothing so much as a round table. Some believe this structure was meant to hold the ashes of fallen SS leaders, whose urns would be placed on the pedestals in the vault. The ceiling of the chamber mirrors the circular depression on the floor, featuring a circle with a swastika inside. The swastika ceiling is physically linked with a sun wheel, made up of intersecting swastikas, incorporated into the marble floor of the Obergruppenführersaal above it. This grand room is a circular hall with twelve columns and twelve niches. This arrangement of iterated round tables redeploys characteristic representations of the Arthurian Round Table, which is almost always regarded from this impossible perspective, from directly above it, through what in film is called a crane shot. Central to the fascist aesthetic is the aerial point of view, the shot from above that freezes movement, dynamism, flux into static posturing, individuals into geometric shapes (Finke and Shichtman, 2009, 25-28).

¶ 31 Leave a comment on paragraph 31 0 Himmler, as Höhne tells it, had a very particular agenda. According to Höhne, he ‘had learnt that King Arthur had assembled about the Round Table his twelve bravest and noble knights, with whom he defended the Celtic creed and liberties against the invading Anglo-Saxons. Here was clearly a lesson for the SS. The tale of King Arthur must have impressed Himmler, for he never allowed more than twelve guests to sit at his table. And as King Arthur had chosen his bravest twelve, so Himmler appointed his twelve best Obergruppenführer to be the senior dignitaries of his Order’ (Höhne, 1972, 151). In Himmler’s headquarters—which Höhne calls his Camelot—‘the chosen few would assemble around the Reichsführer’s oaken table in a 100-foot by 145-foot dining hall, sitting in high-backed pig skin chairs, each carrying the name of its owner knight inscribed on a silver plate’ (Höhne, 1972, 152). No one really knows what, if anything, went on in Wewelsburg Castle when Himmler occupied it, but descriptions at least suggest that Himmler planned for it to be the headquarters of something like a chivalric order, complete with initiation rituals and burial ceremonies.

¶ 32 Leave a comment on paragraph 32 0 Höhne writes: ‘Contact with the past was supposed to instill into the SS Order the realisation that they were members of a select band, to lay the foundations of historical determinism, marking out the SS man as the latest scion of a long line of Germanic nobility. Himmler’s “basic features of the SS” laid down that the SS was on the march “in accordance with immutable laws as a National Socialist Order of men of the Nordic stamp and as the oath-bound community of their clans”; it continued: “We would wish to be not only the men who fought of old, but the forebears of later generations essential to ensure the external existence of the Germanic people of Germany”’ (Höhne, 1972, 154). For Höhne, Himmler seems to straddle the fine line between a magnificent madness, imagining himself King Arthur surrounded by a knightly corps of SS commanders, and brilliance, devising an extraordinary propaganda device that allowed for both the historicization and romanticization of the SS—a propaganda device which located the SS’s origin in the chivalric middle ages. Höhne’s narrative argues that Himmler understood knighthood as an institution located both in the antique past and transcendent of historical period—knights could just as well exist in post-depression Germany as they did during the twelfth century. This construction of the knight connects the SS to the medieval past and projects it into the future. Himmler’s fashioning of the knight therefore places this figure at the center of fascist ideology, embodying those qualities that differentiate the select few, the military elite, from all others, the masses. Like knighthood, the SS functions as the elite apparatus by which high culture is determined and transmitted. Theweleit, echoing Benjamin’s assessment of Manetti, writes: ‘The man of culture is defined as the man who knows the difference between first-lieutenant, major, and captain; a barbarian is a man who feels no love either for uniforms or death. And the “highest” form of cultural celebration is war’ (Theweleit, 1987, 2, 63). Himmler’s SS officer saw himself as not only carrying on the tradition of knighthood, but also representing an evolutionary leap forward–with an eye toward the next soldierly paradigm.

¶ 33 Leave a comment on paragraph 33 3 Hitler’s own sentiments regarding the institutions of knighthood, at least as they are reported by one-time confidante Hermann Rauschning, echo Höhne’s description of Himmler. Hitler’s appropriation of the middle ages supplements Himmler’s, marshaling medieval images of knighthood as a means of legitimating genocide. Rauschning reports one conversation in which Hitler muses on the arguments of Joseph Arthur, Comte de Gobineau, a racial ‘scientist’ whose Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races (1853-1855) predicted that racial mixing—and therefore racial decay—was inevitable. According to Rauschning, Hitler remarked: ‘How can we arrest racial decay? … are we to allow the masses to go their way, or should we stop them? Shall we form simply a select company of the really initiated? An Order, the brotherhood of Templars round the holy grail of pure blood?’ (Rausching, 1940, 229).[8] The contradictions implicit in this invocation of the Knights Templar and the holy grail by an erstwhile unemployed postcard painting, flop-house dwelling, beer hall brawling corporal in a defeated army are smoothed over by Hitler’s rereading of Gobineau and racial science. The images of cultural power conjured up by Hitler’s references to the grail and the Knights Templar do not speak to his or his audience’s experiences; they are exotic and tantalizing. He addresses not aristocrats seeking to confirm their privilege, but those who perceive themselves as modernity’s victims, whose conception of the future has been shattered by political and economic hardship. In place of the hard lessons of war and depression, Hitler offers a fantasy in which a dispossessed underclass could fashion itself as a new aristocracy, tracing its roots back to an old medieval aristocracy not through the patrilineage espoused by the medieval aristocracy but through the affinity of blood, through the doctrines of a racial science simultaneously mythologized and historicized.

¶ 34 Leave a comment on paragraph 34 0 Hitler’s exegetical reading of the middle ages is mediated by Richard Wagner, whose music drama, Parsifal, is the subject of the Führer’s lecture. Like Wagner, Hitler transforms Arthurian romance into figural drama. In A Communication to My Friends, Wagner writes:

My studies thus bore me, through the legends of the Middle Ages, right down to their foundation in the old-Germanic Mythos; one swathing after another, which the later legendary lore had bound around it, I was able to unloose, and thus at last to gaze upon its chastest beauty. What here I saw, was no longer the Figure of conventional history, whose garment claims our interest more than does the actual shape inside; but the real naked Man … the true human being (Wagner, [1892] 1966, I: 358).

¶ 36 Leave a comment on paragraph 36 0 Seeking ‘chastest beauty,’ Wagner must move beyond romance, ‘the later legendary lore,’ to find ‘the old-Germanic Mythos.’ He is not interested in ‘conventional history’—the careful historicism located in the pursuit of ‘facts’ that became the gold standard of nineteenth-century scholarship bores him—but rather the Truth, origin, ‘the real naked Man.’ For Wagner, Parsifalembraces history only to transcend it; the music drama looks to the past to find ‘the true human being.’

¶ 37 Leave a comment on paragraph 37 0 Hitler also mythologizes and historicizes his understanding of race through an exegetical reading of Parsifal, which he understands as an historical rendering of the middle ages. Hitler, as Rauschning reports it, maintains that a fascist reading of the text would be an historical one that would strip it ‘of every poetic element,’ to reveal the truth concealed from the uninitiated: that ‘a world-wide process of segregation is going on before our eyes’ (Rauschning, 1940, 230).

We must interpret ‘Parsifal’ in a totally different way to the general conception, … Behind the absurd externals of the story, with its Christian embroidery and its Good Friday mystification, something altogether different is revealed as the true content of this most profound drama. It is not the Christian-Schopenhauerist religion of compassion that is acclaimed, but pure, noble blood, in the protection and glorification of whose purity the brotherhood of the initiated have come together. The king is suffering from the incurable ailment of corrupted blood. The uninitiated but pure man is tempted to abandon himself in Klingsor’s magic garden to the lusts and excesses of corrupt civilization, instead of joining the elite of knights who guard the secret of life, of pure blood. All of us are suffering from the ailment of mixed, corrupted blood. How can we purify ourselves and make atonement? (Rauschning, 1940, 229–230)

¶ 39 Leave a comment on paragraph 39 0 Like Wagner, Hitler does not conceive of Arthurian romance as mere fiction, but as a kind of figurative history. But whereas Wagner may have only suggested, as Martin Shichtman argues, that Parsifal is ‘about a purging of impurities and a return to the happier spiritual days of the past, not only for those who live in the Grail kingdom but also for those in nineteenth-century Germany’ (Shichtman, 1992, 142), Hitler’s interpretation is more focused; he insists that the poetic façade conceals actual historical truths about racial struggle. In this sense he performs a medieval reading of medieval history, an exercise in allegoresis. For Hitler, as for the medieval historian, empirical reality is beside the point. It must be stripped away to reveal the ‘real’ obscured by the fancy dress. What is important is the manner in which history moves—and moves its readers—toward a transcendental objective (Finke and Shichtman, 2004, 18). Of course, Hitler’s transcendental real was not, as it was for Augustine, caritas—divine love—but rather the ‘pure noble blood’ of the Aryan race.

¶ 40 Leave a comment on paragraph 40 1 Rauschning’s Hitler offers a Grail fantasy as a corrective to Nazi anxieties about ‘racial’ contamination, about the corruption of ‘pure’ blood lines. According to Hitler’s interpretation of the Grail legend, Anfortas is suffering from an ‘incurable ailment,’ ‘corrupted blood’; indeed, all endure ‘the ailment of mixed, corrupted blood.’ Klingsor’s magic garden reproduces, as the Führer tells it, the modern world’s ‘lusts and excesses of corrupt civilization.’ In opposition to the contaminated, Hitler places his brotherhood of Grail knights. Only by correctly interpreting the old narratives and following the canons of behavior set down by the aristocracy of the antique past can twentieth-century Aryans create a new paradigm to counter the decadence of modernity: ‘The eternal life granted by the grail is only for the truly pure and noble! … Only a new nobility can introduce the new civilisation to us. … Those who see in the struggle the meaning of life, gradually mount the steps of a new nobility. Those who are in search of peace and order through dependence, sink, whatever their origin, to the inert masses. The masses, however, are doomed to decay and self-destruction’ (Rauschning, 1940, 229–230). The redundancy in Hitler’s discourse points, dramatically, we think, to the obsessiveness of his program to promote a new kind of man, an elite warrior, ‘a select company of the really initiated,’ ‘a new nobility.’

¶ 41 Leave a comment on paragraph 41 0 Hitler speaks of ‘pure, noble, blood, in the protection and glorification of whose purity the brotherhood of the initiated have come together.’ Purification must come, Hitler tells us, from ‘selection,’ ‘segregation,’ ‘leaving the sick person to die.’ Can there be any doubt here about the identity of the impure to whom Hitler refers? The language used to separate the elect from the diseased is precisely the language the Nazis used to differentiate those who would live and those bound for the gas chambers. A 1926 speech by Julius Streicher, editor of der Stürmer, an early, antisemitic, pro-Nazi newspaper, isolates the source of the pollution about which Hitler speaks: ‘There are three types of parasitic Jews. You will be familiar with the first type: their home is the bank, from whence they practice their economic extortions on their host nations. The second variety is equally widely known. These are the Jews one invariably sees sitting with blonde German girls in bars and cafes, sapping the sexual and racial strength of their host people and destroying them. But there is also a third type of Jew—the kind who quite literally sap the blood of Gentiles and their children. They do so not for religious reasons, but because their own chaotic blood is in danger of decomposition; it is only in sucking the blood of other peoples that they can preserve their own life’ (Theweleit, 1987, 2: 9–12). In this speech Jews are portrayed as vampires who survive by contaminating others–economically, sexually, and racially. They are a disease that infects their host.[9] Hitler, according to Rauschning’s recollection, fantasizes about a new Grail knight who will purge such pollution from the system of the state; he will cleanse the organism.

¶ 42 Leave a comment on paragraph 42 3 How much different is this Nazi knight from his medieval counterpart? The introduction of the Holy Grail into Rauschning’s eyewitness account reminds readers of medieval literature that romances such as Chrétien de Troye’s Conte du Graal, Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival, and the Queste del Saint Graal contain numerous references to Jewish responsibility for the crucifixion of Christ. While these references seem largely gratuitous, their repetition suggests that the authors of these texts were not only unreflectively mimicking medieval church doctrine. In glorifying the values of their knightly patrons by placing Christian chivalry in opposition to Jewish collective guilt, they reinforced popular beliefs about Jewish contamination—that Jews polluted wells and caused diseases like the plague, that, vampire-like, they murdered Christian children for their blood—and advanced a political agenda in which the condemnation of an already disenfranchised minority served to reinforce the power and authority of a hypermasculine military ruling class. Norman Cohn, in fact, argues that the twelfth century brought about a significant shift in European antisemitism: ‘It was in the twelfth century that [Jews] were first accused of murdering Christian children, of torturing the consecrated wafer, and of poisoning the wells . … But above all it was said that Jews worshipped the Devil, who rewarded them collectively by making them masters of black magic; so that however helpless individual Jews might seem, Jewry possessed limitless powers for evil’ (Cohn, 1966,22).

¶ 43 Leave a comment on paragraph 43 2 Throughout the twelfth and thirteenth centuries—at the height of the production of both Arthurian history and romance—persecutions against Jews were carried out across Europe. Guibert of Nogent writes of the massacre at Rouen, where crusaders ‘herded the Jews into a certain place of worship, rounding them up either by force or by guile, and without distinction of age or sex put them to the sword’ (Moore, 1987, 29). Other massacres occurred in such places as Mainz, Cologne, Trier, Metz, Bamberg, Regensberg, and Prague. In many of these cities, townspeople, at least initially, supported Jewish neighbors and assisted them in protecting property. As Moore notes, the massacres ‘were not the work of “the people” but of crusading armies composed of mounted knights and led by nobles’ (Moore, 1987, 117-118). The massacres were the work of those who commissioned Arthurian history and romance. Like their medieval predecessors, Nazis produced their own strategies for displacing their excesses into chivalric adventures. For Dwinger, Himmler, and Hitler, knighthood promoted a genealogy of the blood and demanded the ruthless destruction of all those who posed the threat of contamination. Their notion of a knightly response to Jews—whom Hitler, even as he prepared for suicide, inveighed against as ‘the universal poisoner of all peoples’—and other ‘undesirables’ included gas chambers and crematoria (Berenbaum, 1993, 191). When asked to offer his first impression of the Auschwitz death camp, Elie Wiesel remarks, ‘I was young, and I simply refused to believe my eyes and ears. I thought … We are living in the twentieth century, after all; Jews are not burned anymore. The civilized world would not allow it. My father walked alongside me on my left, his head bowed. I asked him: “The Middle Ages are behind us, aren’t they, Father, far behind us?” He did not answer me’ (Wiesel, [1968] 1995, 139). Medieval warriors and SS men—in their Hugo Boss uniforms—fashioned themselves, idealized themselves, as ‘shining knights,’ even as they performed unspeakable acts of genocide.

About the Authors

¶ 44 Leave a comment on paragraph 44 0 Martin B. Shichtman is Director of Jewish Studies and Professor of English Language and Literature at Eastern Michigan University. With Laurie A. Finke, he has written Cinematic Illuminations: The Middle Ages on Film and King Arthur and the Myth of History. He is co-editor, with James P. Carley, of Culture and the King: The Social Implications of the Arthurian Legend, and, with Laurie A. Finke, of Medieval Texts and Contemporary Readers. He has also authored numerous articles on medieval literature, contemporary literary theory, and film (E-mail: mshichtma1@emich.edu).

¶ 45 Leave a comment on paragraph 45 0 Besides her work with Martin Shichtman, Laurie A. Finke, Professor of Women’s and Gender Studies at Kenyon College, is one of the editors of the Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism and author of Feminist Theory, Women’s Writing and Women’s Writing in Middle English. She has published in Exemplaria, Theatre Journal, Theatre Survey, Arthuriana, and Signs (E-mail: finkel@kenyon.edu).

- ¶ 46 Leave a comment on paragraph 46 0

- [1] On the relation of fantasy to social reality, see Louise Fradenburg who argues that, far from separating us from reality, fantasies have the power to remake the social realities we live and desire (Fradenburg, 1996, 206–208).

- [2] The insight that the knight was an assemblage that fused man, horse, armor, and weapons into a single ‘identity machine’ is Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s (2003, 46).

- [3] The term is E. Jane Burns’ (2002, 25).

- [4] ‘Religion and politics are not within the legitimate province of the Institution … for although Masonry eschews atheism and insubordination, and teaches its youthful Craftsman to reverence the Deity and obey the powers that be, yet it is a principle of its organization to conform itself to the religious and political institutions of the different nations in which it exists’ (Stewart, 185, iii).

- [5] Initiation rituals for the various degrees of Masonry draw heavily upon Old Testament narratives.

- [6] In Masonic mythology, Hiram Abif was the stonemason who built the Temple of Solomon.

- [7] Literally, since today Wewelsburg is a museum, complete with an exhibition on the castle from 1933-1945 (Wewelsburg District Museum, http://www.wewelsburg.de/en/).

- [8] Historians have been uncomfortable with Rauschning’s accuracy as an eyewitness, nervous about the excesses and biases he brings to his historical performance, the possibility that he exaggerated both his friendship with Hitler and his account of Hitler’s conversations. We would argue that it does not matter whether these words belong, finally, to Nazi leader or Nazi stooge; Nazi medievalism was not the fantasy of a single individual, but part of an ideology that pervaded German life. Rauschning’s account, even if it does not tell exactly what Hitler really said, is consistent with—and illuminates—that ideology.

- [9] Nazi fear of sexual pollution is reflected in the belief that Jews were the source of syphilitic infection. Novels of the period, such as Zoberlein’s Befehl des Gewissens (Conscience Commands), warn of Judenpest (Jewish pox), a sexually transmitted blood disease—syphilis—that causes sterility; see Theleweit (1987, 2: 13-15).

Notes

¶ 47 Leave a comment on paragraph 47 0 1. On the relation of fantasy to social reality, see Louise Fradenburg who argues that, far from separating us from reality, fantasies have the power to remake the social realities we live and desire (Fradenburg, 1996, 206–208).

¶ 48 Leave a comment on paragraph 48 1 2. The insight that the knight was an assemblage that fused man, horse, armor, and weapons into a single ‘identity machine’ is Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s (2003, 46).

¶ 49 Leave a comment on paragraph 49 0 3. The term is E. Jane Burns’ (2002, 25).

¶ 50 Leave a comment on paragraph 50 0 4. ‘Religion and politics are not within the legitimate province of the Institution … for although Masonry eschews atheism and insubordination, and teaches its youthful Craftsman to reverence the Deity and obey the powers that be, yet it is a principle of its organization to conform itself to the religious and political institutions of the different nations in which it exists’ (Stewart, 185, iii).

¶ 51 Leave a comment on paragraph 51 0 5. Initiation rituals for the various degrees of Masonry draw heavily upon Old Testament narratives.

¶ 52 Leave a comment on paragraph 52 0 6. In Masonic mythology, Hiram Abif was the stonemason who built the Temple of Solomon.

¶ 53 Leave a comment on paragraph 53 0 7. Literally, since today Wewelsburg is a museum, complete with an exhibition on the castle from 1933-1945 (Wewelsburg District Museum, http://www.wewelsburg.de/en/).

¶ 54 Leave a comment on paragraph 54 0 8. Historians have been uncomfortable with Rauschning’s accuracy as an eyewitness, nervous about the excesses and biases he brings to his historical performance, the possibility that he exaggerated both his friendship with Hitler and his account of Hitler’s conversations. We would argue that it does not matter whether these words belong, finally, to Nazi leader or Nazi stooge; Nazi medievalism was not the fantasy of a single individual, but part of an ideology that pervaded German life. Rauschning’s account, even if it does not tell exactly what Hitler really said, is consistent with—and illuminates—that ideology.

¶ 55 Leave a comment on paragraph 55 0 9. Nazi fear of sexual pollution is reflected in the belief that Jews were the source of syphilitic infection. Novels of the period, such as Zoberlein’s Befehl des Gewissens (Conscience Commands), warn of Judenpest (Jewish pox), a sexually transmitted blood disease—syphilis—that causes sterility; see Theleweit (1987, 2: 13-15).

References

¶ 56 Leave a comment on paragraph 56 0 Benjamin, W. 1986. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. In Illuminations, ed. H. Arendt, trans. H. Zohn, 217–251. New York: Schocken Books.

¶ 57 Leave a comment on paragraph 57 0 Berenbaum, M. 1993. The World Must Know: The History of the Holocaust as Told in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. New York: Little, Brown, and Co.

¶ 58 Leave a comment on paragraph 58 0 Boswell, J. 1980. Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality: Gay People in Western Europe from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Fourteenth Century. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

¶ 59 Leave a comment on paragraph 59 0 Burns, E. J. 2002. Courtly Love Undressed: Reading Through Clothes in Medieval French Culture. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

¶ 60 Leave a comment on paragraph 60 0 Cohen, J.J. 2003. Medieval Identity Machines, Medieval Cultures 35. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

¶ 61 Leave a comment on paragraph 61 0 Cohn, N. 1966. Warrant for Genocide. The Myth of the Jewish World-Conspiracy and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. New York: Harper and Row.

¶ 62 Leave a comment on paragraph 62 0 Finke, L. A. and M. B. Shichtman. 2004. King Arthur and the Myth of History. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

¶ 63 Leave a comment on paragraph 63 0 Finke, L. A. and M. B. Shichtman. 2009. Cinematic Illuminations: The Middle Ages on Film. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

¶ 64 Leave a comment on paragraph 64 0 Fradenburg, L. O. 1996. ‘Fulfild of fairye’: The Social Meaning of Fantasy in the Wife of Bath’s Prologue and Tale. In The Wife of Bath, ed. Peter Beidler, 205–20. Boston, MA: Bedford Books.

¶ 65 Leave a comment on paragraph 65 0 Golomshtok, Igor. 1990. Totalitarian Art: in the Soviet Union, the Third Reich, Fascist Italy, and the People’s Republic of China. London: Collins Harvill.

¶ 66 Leave a comment on paragraph 66 0 Höhne, H. 1972. The Order of the Death’s Head: The Story of Hitler’s SS, trans. R. Barry. London: Pan Books.

¶ 67 Leave a comment on paragraph 67 0 Melzer, R. 2004. In the Eye of a Hurricane: German Freemasonry in the Weimar Republic and the Third Reich. Trans. J. Karnahl. In Freemasonry in Context: History, Ritual, Controversy, ed. A. de Hoyos and S.B. Morris, 89–104. Lanham, MA: Lexington Books.

¶ 68 Leave a comment on paragraph 68 0 Moore, R. I. 1987. The Formation of Persecuting Society. Oxford: Blackwell.

¶ 69 Leave a comment on paragraph 69 0 Rauschning, H. 1940. The Voice of Destruction. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

¶ 70 Leave a comment on paragraph 70 0 Rhodes, A. 1976. Propaganda. The Art of Persuasion: World War II. New York: Chelsea House Publishers.

¶ 71 Leave a comment on paragraph 71 0 Shichtman, M. B. 1992. Wagner and the Arthurian Tradition. Approaches to Teaching the Arthurian Tradition, ed. M. Fries and J. Watson, 139–142. New York: MLA.

¶ 72 Leave a comment on paragraph 72 0 Sontag, S. 1980. Under the Sign of Saturn. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux.

¶ 73 Leave a comment on paragraph 73 0 Stewart. K. J. 1851. The Freemason’s Manual: A Companion for the Initiated Through all the Degrees of Freemasonry. Philadelphia, PA: E. H. Butler.

¶ 74 Leave a comment on paragraph 74 0 Theweleit, K. 1987. Male Fantasies. Trans. S. Conway. 2 vols. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

¶ 75 Leave a comment on paragraph 75 0 Wagner, R. [1892] 1966. Richard Wagner’s Prose Works. Trans. W. Ashton Ellis. 6 vols. New York: Bronde.

¶ 76 Leave a comment on paragraph 76 0 Wiesel, E. [1968] 1995. A Plea for the Dead. In Art from the Ashes. A Holocaust Anthology, ed. L.L. Langer. New York: Oxford University Press.

I love “Shwartzeneggian in physique”.

I mean “Shwatrzeneggerian.” oops:o)