Four: Preservation

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 Access to data tomorrow requires decisions concerning preservation today. — Blue Ribbon Task Force on Sustainable Digital Preservation and Access

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 Despite real technical obstacles, digital preservation is ultimately a challenge demanding social (above and beyond the purely technological) solutions. – Matt Kirschenbaum, Mechanisms

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 3 Having explored the ways that authorship, authority, and interaction will of necessity change as we establish and come to depend upon new networked publishing systems, we must also think carefully about how those systems, and the texts that we produce within them, will live on into the future. Absent a printed and bound object that we can hold in our hands, many of us worry, and not without reason, about the durability of the work that we produce; having opened a word-processing document only to find it hopelessly corrupted, having watched a file seemingly evaporate from our computers, having possibly even suffered a massive hard disk failure, we are understandably nervous about committing our lives’ work to the ostensibly intangible, invisible bits inside the computer. So goes the conventional wisdom of inscription and transmission: the more easily information can be replicated and passed around, the less durable its medium becomes. The post-Gutenberg form of print-on-paper provided vast improvements in our cultural ability to reproduce and distribute texts, but it’s undeniable that stone tablets promise to last far longer. And so the shift from print into the digital: what we gain in ease and speed of copying and transmission, we apparently lose in permanence; the ephemeral nature of digital data threatens our cultural and intellectual heritage with an accelerated cycle of evanescence.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 2 To an extent, this conventional wisdom is correct: we do need to think seriously about how we preserve and protect the key digital documents and artifacts that we are in the process of creating. As I explored in the introduction, early hypertexts such as Michael Joyce’s Afternoon provide a case in point; the hardware and software environments necessary to opening these files are by and large vastly out of date, and many licensed users of these texts find themselves unable to read them. This is the kind of scenario that sets off warning bells for many traditional scholars; the idea of a book’s protocols suddenly becoming obsolete — the ink fading from the page, the pages refusing to turn — are unthinkable, and seemingly similar obsolescence in digital environments only confirms one’s worst suspicions about these new “flash in the pan” forms.

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 However, I want to counteract these assumptions from two different directions. The first is simply to note that books are often far more ephemeral than we often assume. Bindings give way and pages are lost; paper is easily marked or torn; and many texts printed before the development of acid-free paper are gradually disappearing from common usefulness.[4.1] And second, by contrast, bits, and the texts created with them, can be far more durable than we think; as Matt Kirschenbaum has convincingly demonstrated in Mechanisms, once written to a hard disk, even deleted data is rarely really gone beyond the point of recovery. It’s important to stress that this durability is of data written to hard disk; removable media such as tapes, floppy disks, and CDs or DVDs tend to be much more fragile. That having been said, all web-based data is, somewhere, and often several somewheres, written to hard disk. And in fact, it’s the internet that transformed the digital text that was most clearly intended to enact and embody the ephemerality of the digital form — William Gibson’s poem, “Agrippa,” published in 1992 on diskette, as a self-displaying, self-consuming, one-read-only artifact — into one of the most durably available texts in network history, by virtue of the ways that it was shared and discussed. The difference in preserving texts in electronic form versus preserving them in print thus does not entirely hinge on the ephemerality of the newer medium itself, given what Kirschenbaum calls “the uniquely indelible nature of magnetic storage,” pointing to the testimony of “computer privacy experts like Michael Colonyiddes” who argue that “Electronic mail and computer records are far more permanent than any piece of paper” (Kirschenbaum 51). Rather, the difference has to do with our understandings of those media forms, the ways we use them, and the techniques that we have developed to ensure their preservation. We have centuries of practice in preserving print – means of collecting and organizing print texts, means of making them accessible to readers, means of protecting them from damage, all standardized across many libraries with frequently redundant collections. But it took centuries to develop those practices, and we simply do not have centuries, or even decades, to develop parallel processes for digital preservation. We now must think just as carefully, but much more quickly, about how to develop practices appropriate to the preservation of our digital heritage.

¶ 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0

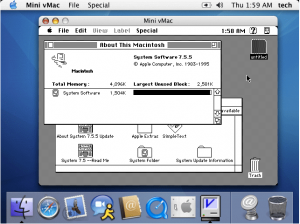

The paradox, as Kirschenbaum demonstrates, is that digital storage media are frequently far more durable than we think; it’s the ways that we understand and treat stored data that produce the appearance of the ephemerality of digital artifacts. Afternoon still exists, after all, in many different forms and locations; what has been lost is not the text, or even that text’s legibility, but our transparent ability to access that text. To read Afternoon on a contemporary Macintosh, we need access to an emulator, a software package that re-creates the conditions under which Afternoon and other such early hypertexts were run when they were originally released. Numerous emulators exist for various hardware and software configurations, and some of them are in fact produced by the original manufacturers, in order to keep their systems reverse-compatible; Rosetta, for instance, is an emulator produced and distributed by Apple as a part of Mac OS X, allowing contemporary Intel-based processors to run software written for older PowerPC machines. But Rosetta does not allow those processors to run programs that were originally written for systems older than OS X; those programs were until recently accessible through “Classic” mode, an OS 9 emulator contained within OS X systems prior to 10.5. Since the release of OS 10.5, there has been no available emulator within which one can run OS 9 programs. Apple’s desire — a generalized desire throughout the computer industry — to move users to newer systems by deprecating older ones (thus minimizing the number and range of systems for which they are required to provide support) suggests that we will need to look to sources other than the manufacturers in order to ensure access to older systems. And in fact many emulators for older systems have been created by fans of the now-outdated texts and platforms to which the emulators allow access, such as the range of Z-machine interpreters that allow contemporary users to play a number of text-adventure games that date back as far as the late 1970s. One might also see Mini vMac, a program that emulates the environment of a Mac Plus (circa 1986-1990) within a window of a contemporary OS X machine [see screenshot 4.1].

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 As Nick Montfort and Noah Wardrip-Fruin note in their white paper on preserving electronic literature, “[a]s long as some strong interest in work from certain older platforms remains, it is likely that emulation or interpretation of them will be an option – new emulators and interpreters will continue to be developed for new platforms” (Montfort and Wardrip-Fruin). The wide availability of such emulators and their ability to resurrect decades-old software and texts on contemporary systems suggest that our concerns about the digital future should be shifted away from fears about the medium’s inherent ephemerality; instead, we need to focus our attention on ensuring that the digital texts we produce remain accessible and interpretable, and that the environments those texts need to operate within remain available.[4.2]

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 My suggestion that digital media texts and technologies are less short-lived than we think should not be interpreted to mean that we can be cavalier about preservation, however, or that we can put off decision-making about such issues for some more technologically advanced future moment. As a recent report from the Blue Ribbon Task Force on Sustainable Digital Preservation and Access suggests,

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 In the analog world, the rate of degradation or depreciation of an asset is usually not swift, and consequently, decisions about long-term preservation of these materials can often be postponed for a considerable period, especially if they are kept in settings with appropriate climate controls. The digital world affords no such luxury; digital assets can be extremely fragile and ephemeral, and the need to make preservation decisions can arise as early as the time of the asset’s creation, particularly since studies to date indicate that the total cost of preserving materials can be reduced by steps taken early in the life of the asset. (BRTF 9)

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 1 Though I would argue that the appeal to the fragility and ephemerality of digital assets is a bit of a red herring, I would certainly agree that we cannot save money now by deferring preservation practices until they’re needed; planning for the persistent availability of digital resources as part of those resources’ process of creation will provide the greatest stability of the resources themselves at the least possible cost. In order to make such advance planning possible, however, we must genuinely “understand the nature of what is being collected and preserved, and where the most significant challenges of digital preservation finally lie” (Kirschenbaum 21), a set of understandings that will require the collective insight and commitment of libraries, presses, scholars, and administrators. These understandings will likely also be subject to a great deal of flux; Clifford Lynch compellingly argued in 2001 that we did not then “fully understand how to preserve digital content; today there is no ‘general theory,’ only techniques” (Lynch). These techniques, which include hardware preservation, emulator creation, and content migration, have begun to coalesce into something of a theory, but we have a long way yet to go before that theory is sufficiently generalized that we can consider the problem solved. And perhaps that theory will never be as fully generalized as it has become for print, in part because of the multiplicity of systems on which digital artifacts run, and in part because, as computer users know all too well, technologies, formats, and media will all continue developing out from under us, and so techniques that appear cutting-edge today will be hopelessly dated some years from now. We absolutely must not throw up our hands at that realization, however, and declare the problem intractable; we can and should take steps today to ensure that texts and artifacts produced and preserved under today’s systems remain interoperable with or portable to the systems of tomorrow.

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 While questions surrounding digital preservation of course present us with a range of thorny technical issues, I want to argue here, following Matt Kirschenbaum, that their solutions are not predominantly technical in nature. In fact, the examples presented by the emulators I mention above may help us recognize that what we need to develop in order to ensure the future preservation of our digital texts and artifacts may be less new tools than new socially-organized systems, systems that take advantage of the number of individuals and institutions facing the same challenges and seeking the same goals. Fans have kept games like Zork and Adventure alive for thirty years, across a vast range of platforms and operating systems, by responding to a communal desire for those texts and sharing the tools necessary to run them. Preservation, I will suggest in what follows, presents us with technical requirements but overwhelmingly social solutions. D.F. McKenzie argued in Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts that the book “is never simply a remarkable object. Like every other technology it is invariably the product of human agency in complex and highly volatile contexts” (4). Context is equally important, and equally volatile, in shaping our understanding of the production, circulation, and preservation of digital texts. The library, for instance, in this understanding, is not simply a building (or a computer server) in which texts are housed, but a social space through which texts circulate, and within which communal efforts toward preservation will find the greatest success.

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 As a recent report by the Council on Libraries and Information Resources notes, however, it is likely that “the library of the 21st century will be more of an abstraction than a traditional presence” (No Brief Candle 8); substantive changes within the library and the ways it works with the academy have already begun. For that reason, in contrast to the other chapters in this text, in which I argue that we as scholars need to make a concerted effort to change something about our institutions and the ways we work within them, I am here instead describing an incompletely understood series of changes already more or less underway within our libraries. It should not come as any surprise that librarians are, for the most part, way out ahead of most of the academy on these issues; as Richard Lanham has noted, the library in its preservation function “has always operated with a digital, not a fixed print, logic. Books, the physical books themselves, were incidental to the real library mission, which was the dispersion of knowledge” (Economics of Attention 135). Thus the transformations of many MLS (Masters of Library Sciences) programs into MLIS programs, offering a degree in Library and Information Sciences, might be seen as emblematic of the ways in which the library and its professionals have long since begun to grapple with the new systems digital communication and its preservation require. But in order for those librarians to successfully face the challenges before them, they require broad support from across the academy; scholars and administrators alike must understand something of the ways that digital library systems work, and of how we might best work within those systems, in order to ensure that the digital collections that we use in our research and the digital objects that we produce as a result of that research will be persistently and usefully available into the future. Where my advocacy comes in, then, it is in service to producing changes in our understanding of the library and how it functions, in order that we might conceive of our projects in ways that best work within the library’s developing information systems, and in order that we might help support the library as it moves into the digital age.

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 There is of course no lack of resistance, particularly amongst the faculty, and particularly within the humanities, to the ways in which the library is changing. Many of these changes, unfortunately, are worth being concerned about, as they stem less from modernization than from contemporary budget crises. Within many institutions, including my own, the library has begun both the deaccessioning of print copies of journals to which we have digital access and the displacement of large portions of the remaining print collections to off-site facilities. These are developments that the faculty would do well to be concerned about; thinning and storing a collection should always be undertaken in a thoughtful, well-considered way. In the case of deaccessioning of print materials, for instance, caution demands that at least one clean print copy remain available somewhere within a library consortium in the event that a text needs to be redigitized, and care needs to be taken that contracts with digital journal providers allow for post-cancellation access to texts released during the period that a library maintains a subscription.[4.3] Similarly, moving print materials off-site (a necessity for many over-crowded libraries, if their collections are to continue to grow) must be done in a similarly thoughtful manner, taking careful account of the ways those materials will be protected and accessed. As faculty, we have a stake in ensuring that these changes are managed in the best ways possible — but throwing up roadblocks in front of such changes would be counter-productive, either causing the library to become unable to grow and develop or reducing the faculty’s future input into such development. Instead, we need to figure out how best to work with the library in order to ensure that the richness of our scholarly archives — whatever their medium — is preserved and protected.

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 The need for faculty input into the preservation of digital resources is even more pressing; though the bulk of the work of preserving digital texts will fall to the library, we all have a share in it, and we all must be aware of the issues. The recent Blue Ribbon Task Force report exploring the options for economically sustainable digital preservation wound up concluding that “[T]he mantra ‘preserve everything for all time’ is unlikely to be compatible with a sustainable digital preservation strategy. The mechanism for aligning preservation objectives with preservation resources is selection — determining which materials are ‘valuable enough’ to warrant long-term preservation” (BRTF 21). This somewhat fatalistic vision, suggesting that we as scholars will need to compete to make sure our resources are seen as “valuable enough,” runs counter to a couple of well-ingrained scholarly principles: that we cannot know today what will be important tomorrow, and as a result, that everything has potential intellectual value. Storage is inexpensive, and there are choices that can be made in the process of developing digital resources that can help make their preservation easier. Even more, there are ways that we can and should begin to mobilize community resources such that many stakeholders with a wide range of investments help support the preservation of the objects we are now building. As Montfort and Wardrip-Fruin argue,

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 Preservation is always the work of a community. Ultimately, preserving electronic literature will be the work of a system of writers, publishers, electronic literature scholars, librarians, archivists, software developers, and computer scientists. But today, and even once such a system is in place, the practices of authors and publishers will determine whether preserving particular works is relatively easy or nearly impossible. (Montfort and Wardrip-Fruin)

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 This chapter is focused on such community-oriented systems and practices; each of the sections that follow takes on one key aspect of the requirements for the digital library by exploring a number of representative projects or technologies. In the process, I’ll look at three different issues with respect to preservation, including the need to develop commonly held standards for markup, so that texts are produced in a format that will remain readable in and portable to new platforms as they arise; the need to provide sufficiently rich metadata for our texts, such that the objects we create will be flexibly findable through search engines and other means, including developing stable locators that will allow texts to be retrievable into the future, regardless of the changing structures of our institutional websites; and the need to provide continued access to digital objects, ensuring that texts themselves remain available when we seek them out. Though I focus on a few particular projects in each of these areas, I want to be clear, however, that this chapter is not advocating for any particular technical solution to the issues facing the library in its drive to preserve our developing digital cultural heritage; instead, what I am more interested in is the fact that each of the technical systems I here describe is at heart a social system, a system that both develops from a collective, community-derived set of concerns and procedures and that requires community buy-in in order to succeed. As Matt Kirschenbaum has argued, “The point is to address the fundamentally social, rather than the solely technical mechanisms of electronic textual transmission, and the role of social networks and network culture as active agents of preservation” (21). Each of the projects I’ll discuss provides a means of investigating the social networks that are developing around issues of preservation, and how those developing social practices can help us understand preservation not as a matter of protecting ephemeral media but rather of making adequate and responsible use of what are in fact surprisingly durable forms of communication.

Is there room somewhere in this discussion to point out that there is an immense (in terms of staff, space, and cost) infrastructure in place already to preserve print? That this structure is entirely invisible to most people, even people heavily involved in print culture? (How many people have been inside a book conservation lab? A bindery?) That the existence of this infrastructure seriously calls into question the idea that ink-on-paper is automatically more durable than bits on hard drive?

Oh, of course — that definitely needs to come in here.